Consumer Spending, While Draining Bank Accounts, Could Prolong Fed Tightening

Economics is a social science, and as such, it’s based largely on human behavior, with mathematical models then used to assess decisions and predict outcomes. The U.S. government published consumer savings rates during the first week of October. The results are in line with what economists would expect when the masses’ ability to live the same lifestyle as before is challenged by either high inflation, fewer jobs, or both. There is a delayed effect on consumers’ behavior in the face of higher prices, this is impacting debt levels and savings rates. Also, the upper echelons of earners are not as inclined to cut back, which could make the Fed’s job trickier.

One recognized principle of economics that has proven true throughout history is related to adding stimulus and taking stimulus away and changes in spending. When more money is put in the hands of the citizenry, whether by tax decreases, or direct stimulus checks, that money will be put to work (spent), fairly quickly. Especially by those whose lives would most be impacted, those with stricter budgets. When discretionary income decreases or prices rise, consumers don’t react as quickly. We can think of the reasons why in this way; one is that fixed costs can’t change as quickly if income goes down as they can if the ability to spend increases. The other reason is that we tend to adjust on the downside more slowly while still doing many things that we can not as easily afford to do.

Put another way, we accelerate spending quickly when money is more available than we brake when it becomes less available; in fact, households tend to take their foot off the accelerator, even if it keeps them spending at a pace that puts their household finances in jeopardy.

The Post-Covid Economy is Confounding

At the turn of the year, consumers were thought to have built up about $2.4 trillion of excess savings during the pandemic. Many economists argued the economy would be able to avoid a recession, even as the Fed aggressively raised interest rates. Many of these economists, joined by business owners and investors, are changing their odds of a soft landing; many are still expecting a quick rebound as consumers are believed to have exited the pandemic in strong financial shape.

New data about U.S. consumer savings, however, and a look at consumer finances suggest that they may be overestimating the long-term resilience of consumers.

Last week the FDIC shed some light on savings rates, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provided information on Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE).

Downward revisions to the savings rate indicated that households had used a much bigger proportion of pandemic savings than seen in previous data, and the starting point is now believed to have been smaller.

According to previous data, through July, households had spent about $270 billion, or 11% of peak excess savings of $2.4 trillion. The updated data show that the peak savings stock was $2.1 trillion. Also, about $630 billion, or 31%, has already been spent.

The $1.4 trillion that is in savings is still no small amount of money. But, Nancy Lazar, chief global economist at Piper Sandler, told Barron’s that it’s not enough to prevent credit-card borrowing from ballooning and consumer delinquencies from climbing. Credit-card loans are now 6% above their pre-pandemic high. With rates climbing, 60% of revolving debt is extending out and being carried for one year or longer.

“Delinquency risk is rising, especially for low-end consumers who have exhausted their excess savings,” Lazar said.

Lazar told the journal that she calculates the composite 30-day delinquency rate across big financial institutions, like American Express (AXP), and JPMorgan Chase (JPM), to have risen to 0.82% at the end of August from 0.78% a year earlier. More evidence comes from data from Kroll Bond Rating Agency that showed subprime auto-loan delinquencies are climbing higher, and even prime auto-loan delinquencies are moving up. And Affirm Holdings (ticker: AFRM), which is a buy-now and pay-later company, reported a 290% year-over-year increase in its provision for credit losses.

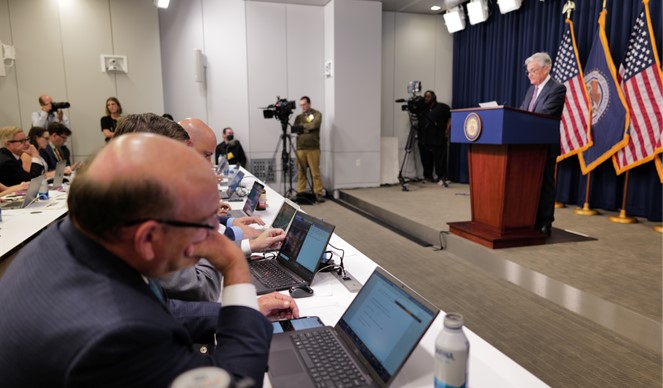

What Fed Governors Want

Is this “bad news” actually “good news” for stocks and bonds? If consumers have lower means than thought when the Fed began its tightening, this could give hope to those investors that are looking for the Fed to pivot back to an easier policy stance. But economics seldom plays out with just one or two inputs.

Another piece of information economists look at is the Labor Department’s Consumer Expenditure Survey data. Overall, 60% of consumption in the U.S. are from the top 40% of income earners. The lowest quintile, the lowest 20% of earners, those with less discretionary income, make up only 9% of consumption in the U.S.

So the Fed’s predicament has them needing to squelch the relatively high level of consumption of the top 40% that can still pay for the same lifestyle without reducing consumption, and at the same time not overly disrupt those that will feel the impact the most, the lowest 20% of earners in the country.

Take Away

It seems that in the broadest sense, the Fed has impacted consumption in the group that will impact consumption least. Those that would impact the pace of the economy and inflation most are not yet putting their wallets away. This increases the degree of difficulty the Fed faces when working to bring inflation down to the 2% target.

Managing Editor, Channelchek

Sources

https://www.kbra.com/sectors/public-finance/issuers

https://www.barrons.com/articles/consumer-savings-fed-problem-51665185301?mod=hp_LEAD_1